Eliminate Knee Pain During Squats

Knee and/or low-back pain are often due to poor lateral stability. Stability, as defined by Charlie Weingroff is, “Control in the presence of change.” Knees collapsing in during single leg exercises like pistol squats, running, or lunging may be a sign of poor lateral stability. Stability at the knee is provided by adequate strength of the muscles of the hip like the glutes and external hip rotators. Knee pain, tendonitis, and chronic tightness in the iliotibial (IT) band are generally symptoms of a movement dysfunction. The repetitive strain of poor movement mechanics leads to tissue inflammation, pain, and adhesions in the connective tissue of the hip and IT-band.

Movement in the Sagittal Plane

Lateral stability comes into play during sagittal plane movements like running that are in a forward direction. The forward movement of running for example is supported by the structures on the sides of the body that are meant to resist or control lateral motion of the knees, hips, and low-back. Knees collapsing inward, hips shifting to one side, and the low-back being unable to resist lateral flexion (side-bending) are all problems of lateral stability. Lateral stability is also called frontal plane stability – the frontal plane represents the sides of the body. Lateral or frontal plane stability is required to support movements like lunging that occur in the sagittal plane (forward or back).

Poor Lateral Stability & Hip Tightness

Limited hip internal rotation is often the result of poor lateral stability. In other words, the hips are tight due to lack of core stability. Flexibility and stability compliment one another – for one joint to be mobile, another joint needs to be stable. When stability is lost at one joint, another joint loses it flexibility – in compensation to create stability elsewhere. Dean Somerset explains in this great blog that:

Limited hip internal rotation correlates to poor lateral stability

Limited hip external rotation correlates to poor anterior core stability

This means that a side-plank (lateral stability) can help improve hip internal rotation and that a front-plank (anterior core stability) can improve hip external rotation.

The Lateral Subsystem

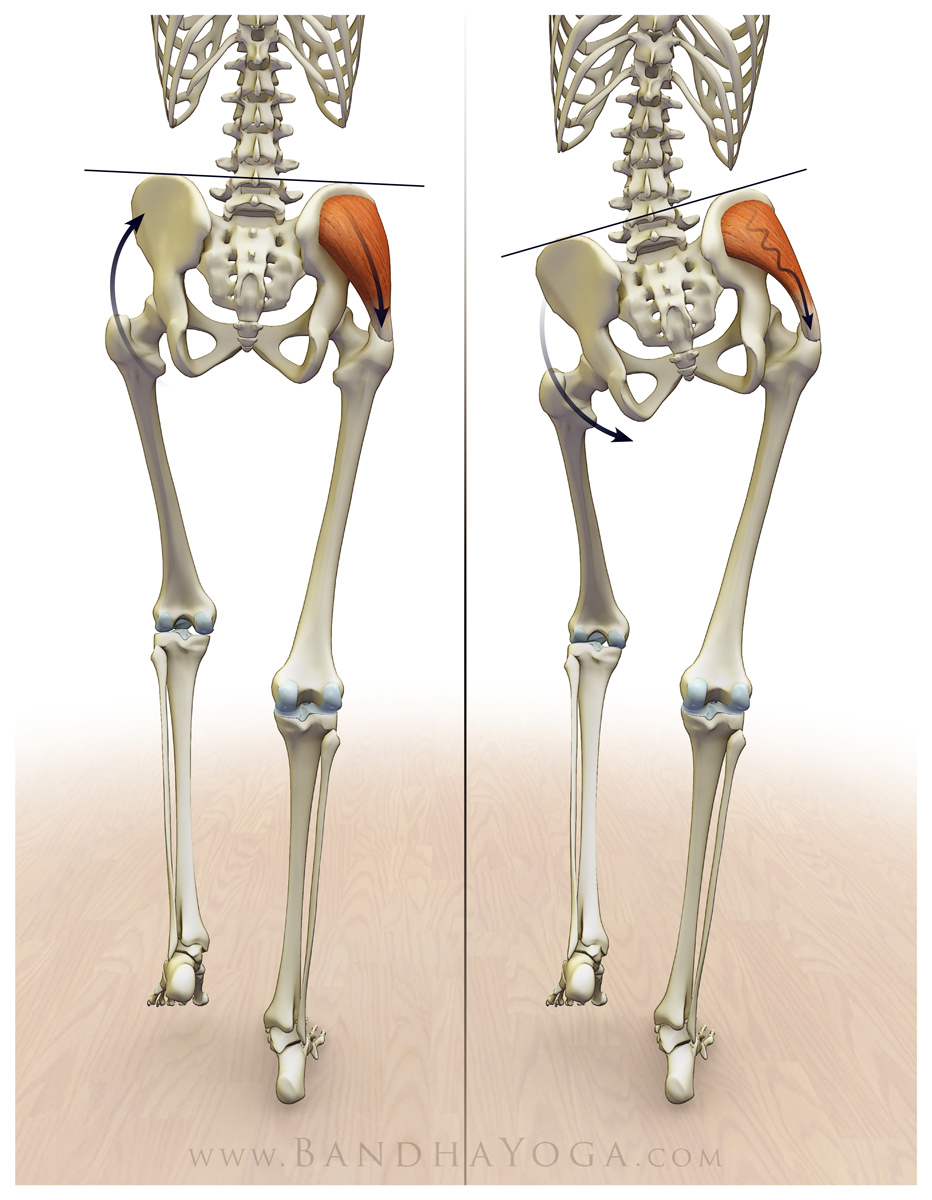

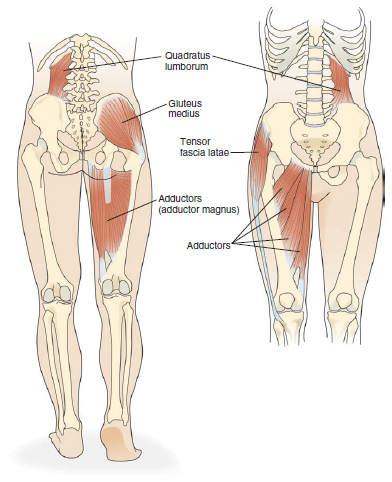

Two important muscles involved in lateral stability are glute medius and quadratus lumborum (QL) of the low-back. During any single leg stance (where weight is transferred to the right leg for example) – the right glute works with the QL on the opposite side to provide stability. During single leg stance the glute medius is responsible for keeping the hips level. A weak or inhibited right glute medius would result in the left hip dropping – the hips tilting to the left. In the illustration below you can also see a right side bend of the lumbar spine accompanying the hip drop. QL spans from the top of the hips to the lumbar spine and lower ribs – resisting this lateral flexion of the spine.

In this example, the left QL and right glute medius, along with the right adductor all work together to provide stability. This referred to as the lateral subsystem (LSS) – QL, glute medius, and the adductors.

During running or lunging inhibition in glute medius is also a factor in knee valgus – the knee collapsing inward. The image below also shows foot pronation – a collapse of the medial arch. Ankle flexibility is outside the scope of this article, but as I mentioned here, ankle dorsiflexion is required for a good knee position. Interesting to note, both QL and glute dysfunction are correlated with ankle sprains. Lack of ankle flexibility impairs the functioning of this system and vice versa.

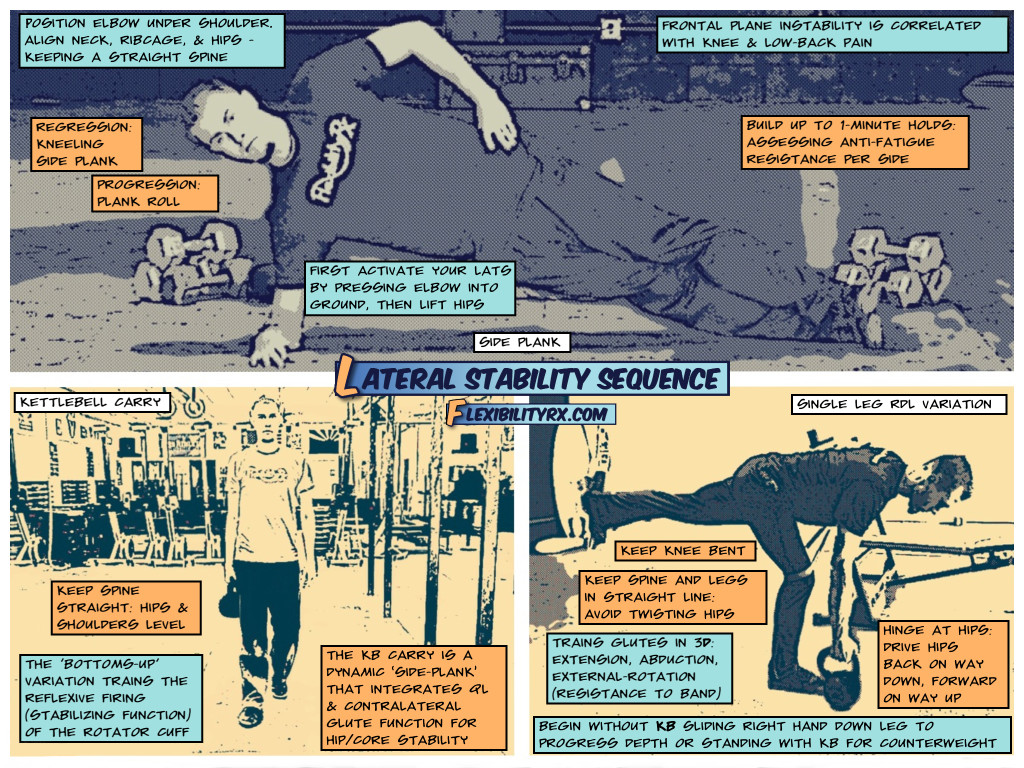

Lateral-Stability Sequence

The lateral stability sequence strengthens QL, the single-leg RDL trains the glutes, while the kettlebell carry integrates QL with contralateral glute function. While the lateral subsystem is not in play as a integrated system during a regular squat, optimizing glute, QL, and adductor function lays a solid foundation for a strong squat. Training muscles as stabilizers during single-leg movements and during core stability exercises transfers well to all of your movements in the gym.

Side Plank

The side plank strengthens QL of the low-back. Athletes should be able to work up to roughly a minute hold per side of the side-plank. The important point in low-back pain is the difference in strength (fatigue resistance) of QL per side. A 5% difference in fatigue resistance per side in the side plank is correlated with low-back pain. This means that while QL may be weak on both sides, identifying an asymmetry is the most important point to correct imbalances. Strengthen the weak side and then focus on holding the side-plank for longer durations or for increased repetitions.

Time your ability to hold a side plank on each side and note the difference in fatigue resistance.

*Note that the top leg can be placed in front of the bottom leg on the floor for the side plank. Also, athletes that are unable to hold a side plank should begin with the bottom knee on the floor (knee bent to 90 degrees). The top leg can be placed out in front like the side plank, but the bent bottom leg (knee on floor) allows for an easier progression.

Single Leg RDL (Variation)

The single leg RDL is one of the best overall exercises for general fitness – a great exercise to incorporate into a warmup. The single leg RDL is a hip dominant single leg exercise that trains the glutes and hip rotators to function as stabilizers of the hip and knee. This is important because many exercises train the glutes and rotators as movers, neglecting their stabilizing function. This exercise is a single leg deadlift with the stance leg bent about 20 degrees. The deadlift like the barbell good morning are different from the squat in that they are hip hinge movements. A hip hinge is a posterior weight shift of the hips with bent knees and a vertical tibia. While the squat takes the hips ‘down and back’, the hip hinge focuses on the posterior shift of the hips – tensioning the hamstrings and placing the weight on the heels.

The exercise pictured is a variation on the traditional single leg RDL. The kettlebell placement for the single leg RDL is normally opposite the stance leg. In this variation the kettlebell is placed on the side of the stance leg to help counter the pull of the band on the knee. Note that this variation doesn’t work very well with just the band. Placing the kettlebell opposite the stance leg is also difficult with the band in the line of path of the kettlebell. You can use this exercise as is or use the traditional RDL with the kettlebell opposite the stance leg.

Tony Gentilcore breaks down the traditional single leg RDL is this great video.

Suitcase (Kettlebell Carry)

The one arm kettle bell carry (suitcase carry) is a great way to strength a weak QL. Another benefit of the suitcase carry is that it activates the lateral subsystem – not only strengthening QL but strengthening the glut medius on the opposite side. This integration of QL and the contralateral glute transfers over to running and other functional activities that require a weight transfer onto one leg.

– Kevin Kula, “The Flexibility Coach” – Creator of FlexibilityRx™

Tags: back pain during squats, joint by joint approach, kettlebell carry, knee pain during squats, lateral stability, lateral subsystem, side plank, Single Leg RDL, suitcase carry

Leave A Reply (No comments so far)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No comments yet